TEXT-ILE

The Eight Foundation and Ahāra present our second collaborative exhibition — an invitation to explore the delicate dance between gestures and utterances, where each piece reflects a profound engagement with words, experiences, poetry, repetition, movement and the very act of making.

When gestures and utterances are seen as processes based on a text/textile axis — the two nodes of an axis that, etymologically linked through the Latin texere (to weave), reflect an intimacy and complexity in their association with making. It is Victoria Mitchell’s ‘textility’ of making that suggests a practice that informs thought. The common associations between text and textile, between utterances and gestures, are what allow for this exhibition’s attempt at rendering limiting words limitless, an exercise in weaving from the fraying edges of language itself.

Conceptually and physically, the show is centred around Jason Wee’s …above the far ships…, a visual poem transcribed into a series of knots based on the dots and dashes of Morse code. Through the use of these knots, Wee not only visualises poetry, but also makes it tactile and tangible. The repetition and the knotting allude broadly to processes of textile-making, and specifically to a history of encoding messages in textiles. Encoded in the form of a haiku, Wee’s poem is about the future of Asia, keeping the many crises, conflicts and dilemmas of our present moment in mind.

Across from Wee, Astha Butail’s large preoccupation with memory, oral traditions and their role in the transmission of cultural values takes up the entire wall. a first short vowel inherent in consonants is a visual representation of these concerns, exploring the letter ‘a’ through 81 frames of various sizes. Butail’s artistic practice has been one marked by meaning-searching and layering; she deals with mnemonic traditions passed down from generations to generations in the form of chants, prayers and poetry. Under the guidance of Sanskrit scholars from South India, she studied parts of the Vedas — an ancient oral tradition from the Indian Subcontinent that were later translated into written works but, according to the artist, very few people today follow either of these paths in understanding ancient thought.

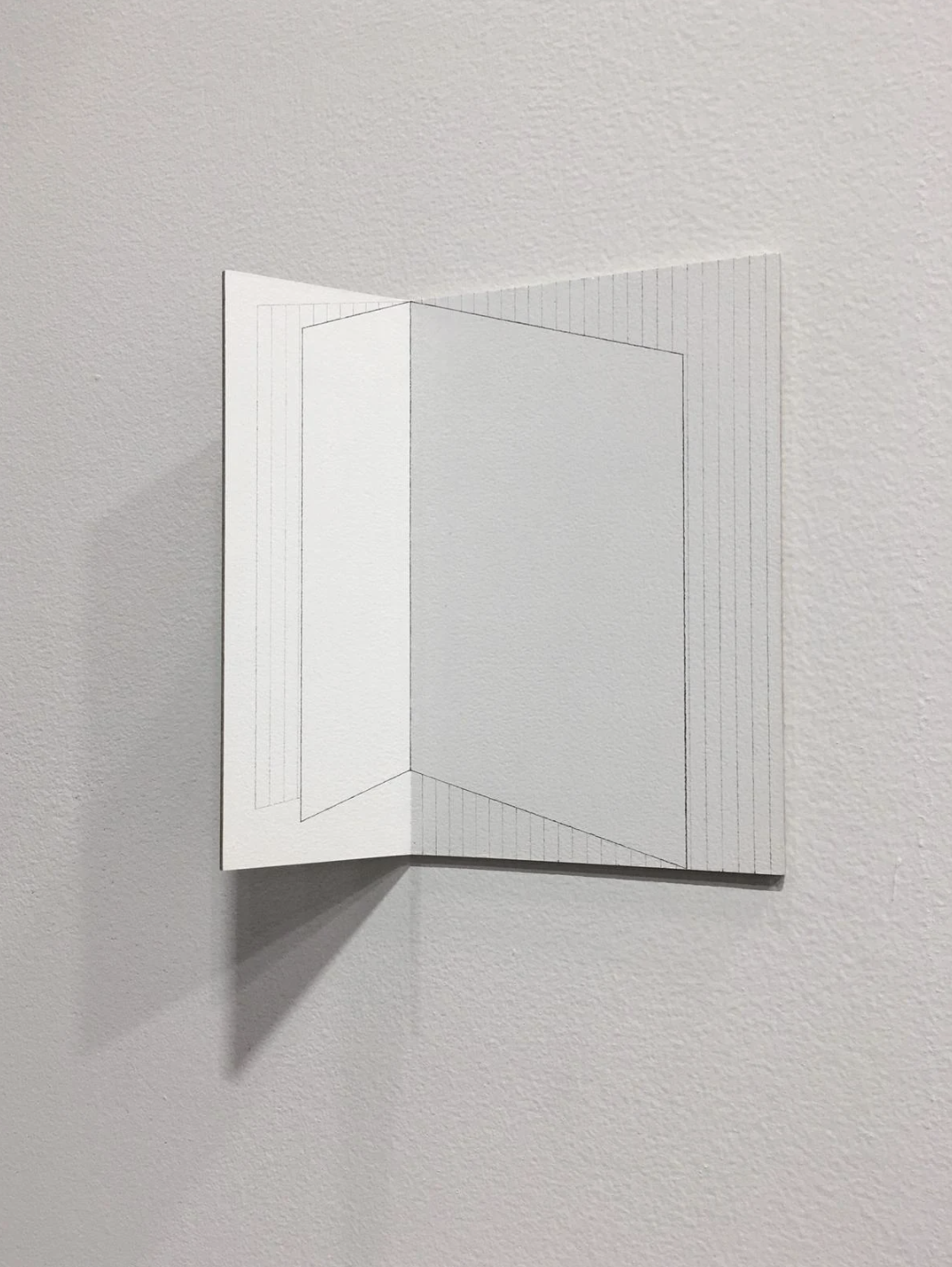

Going beyond the movement in linguistics and literary history — one being the moving from oral traditions to writing them down — there are other movements artists have encapsulated here. Be it the interplay of light and shadow in Jong Oh’s small mixed media installations, or the surfaces of Radhika Khimji’s works that become places to traverse, to cross and make flat, to cut through spaces and map out areas of vastness and emptiness. There is an ebb and flow on the surface, a movement between whether the object is a painting, a drawing or a sculpture, not fitting neatly into one category. In a sense, Khimji avoids being tied down to just one identity — even though everything in her work has a place, she shows the possibility of things shifting and changing, like looking through a kaleidoscope.

Rakhi Peswani has literally stitched together 50 oxymoronic English phrases, with each phrase made up of 2, if not completely opposite, slightly contrasting words. These hand-embroidered words possess a certain qualitative conflict with each other, with oxymorons such as ‘Social Alienation’, ‘Loud Silence’, ‘Blind Eye’ and, most curiously, ‘Moving Stillness’. These paradoxical pairings of words subtly hint at psychic conditions of despondence and despair, and the surfaces on which the words have been stitched (Khadi and Calico cotton) serve as reminders of the particular colonial and social histories of these fabrics in the Indian context.

In Songs of Love and War, Youdhisthir Maharjan almost climactically fuses the two nodes of our axis — text and textile. Instead of metaphorically weaving a story, he has used printed text and books and literally woven an object out of them. Based on his Buddhist and Hindu sensibilities, Youdhi looks at the futility and endlessness of cycles of rebirth and incarnation — a life that seems to have no end or beginning, much like Samuel Beckett’s play Waiting for Godot. It is through this futility, endlessness, repetitive cycles of weaving, erasing, painting, doodling, cutting and burning holes into books that Youdhi makes language lose its value and meaning. He turns the printed word into abstract forms, where language becomes a form of making and the fabric he makes becomes a form of speaking.

Heman Chong’s relationship with the book-object is different. In a heavily redacted folio from Call for the Dead #6, Chong has erased everything from the page except for the verbs. The repeated bureaucratic process of inking out text to hide information is as important as the choice to leave bare the verbs. As if Chong is leaving behind decontextualised traces of something that has happened, something that needs to be stitched together to form a completely new whole.

In Unhappy Together, Renuka Rajiv tells the story of a couple that is unhappy, but chooses to be together through the unhappiness. Rajiv, through drawings, zines, prints, sculptures and, lately, embroidery, tells stories of internal worlds and intimate interactions. Their love for narration and their need to communicate is seen more in the visual, outside the realm of verbal languages. It is a visual world that is reluctant to be written about, yet intent to reach out.

Finally, almost as if taking cue from Youdhi, we come to the beginning of the exhibition, which could also be the end. Shilpa Gupta’s photographs titled I want to live with no fear, use those words as a hook. A lot of Gupta’s work is interactive, where the gap between the artist, the art object and the viewer is intentionally blurred. Using a string of simple yet powerful words hand-written on 3,000 balloons tied to strings, Gupta elicited simple yet powerful responses from the viewers and participants of the work. “I want to live with no fear” became an essential, simple, universal thought that many identified with.

Curation and text by The Eight Foundation